Articles > Published Studies > Uraan Nilaimaikkarars: A Historical and Sociocultural Analysis of an Aristocratic Nadar Subsect.

Uraan Nilaimaikkarars: A Historical and Sociocultural Analysis of an Aristocratic Nadar Subsect.

Published Studies

Featured

First published: December 14, 2025

|

Last updated: December 25, 2025

Introduction

The Uraan Nilaimaikkarars, or Nilaimaikkarars, are a subsect of powerful aristocrats within the Nadar community. In 1639 AD, ten Nilaimaikkarar rulers, known as the Nadadhi Nadakkal, were vested with authority over the northern divisions of Manadu. This essay explores the traditions, customs, and privileges of the Nilaimaikkarars, as well as the administrative authority exercised by the ten Nilaimaikkarar rulers appointed by the Madurai Nayak ruler. It further examines the tension between Madurai Nayak sovereignty and the Nadar community. This article is based on the research contributions of Mr. S. Ramachandran, Dr. A. Thasarathan, Mr. A. Ganesan, and Robert L. Hardgrave Jr.

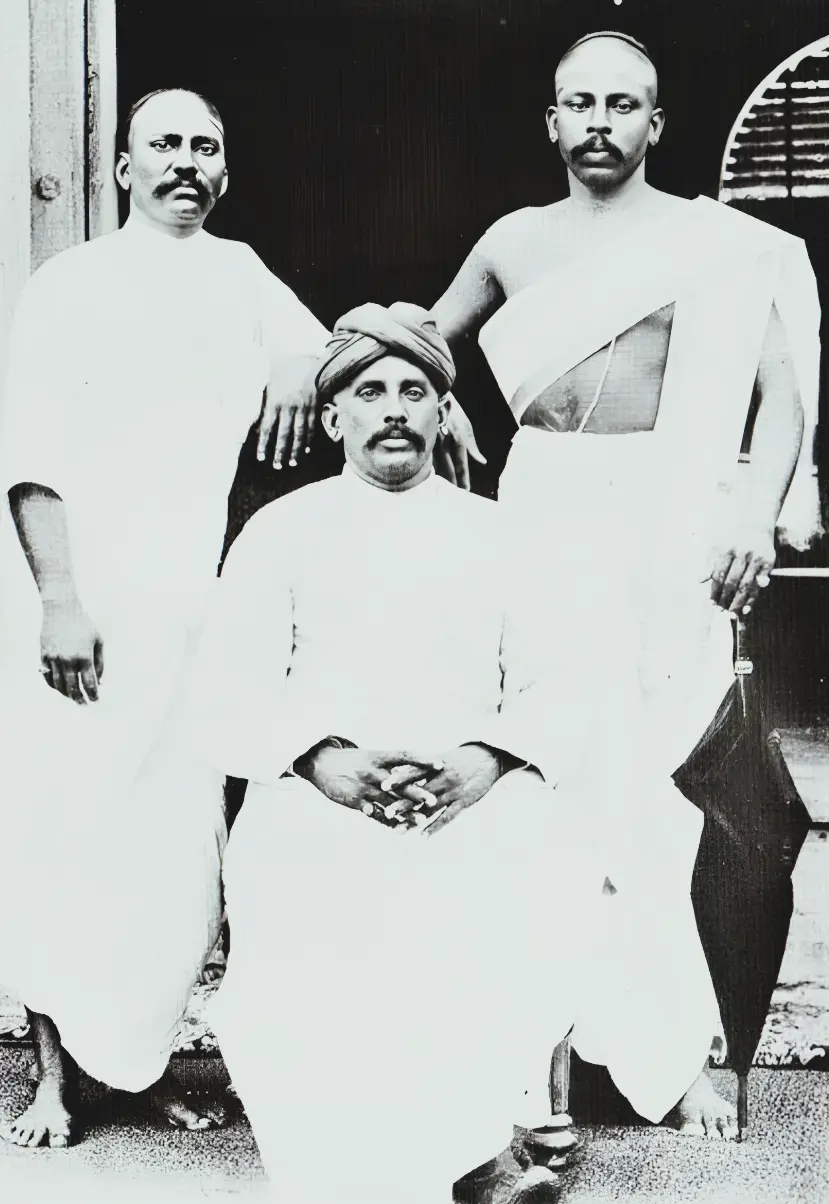

Nilamaikkarars of Kayamozhi, circa 1900.

Who are the Uraan Nilaimaikkarars?

The Uraan Nilaimaikkarars (pronounced as Ūrāṉ Nilaimaikkārar), or Nilaimaikkarars, are a subsect of powerful aristocrats within the Nadar community who historically controlled vast tracts of land and predominantly lived in the regions south of Tirunelveli, including present-day Kanyakumari district. Historical observers of the 19th-century and subsequent scholars, including Dennis Templeman, note that the Nilaimaikkarars constituted the highest division within the old Shanar community.

Etymology

A mid-18th-century inscription from Kulasekarapattinam, Tiruchendur taluk, now part of Thoothukudi district, records the Nadar subsect Uraan Nilaimaikkarar. Uran (pronounced Ūraṉ) was originally a term used during the Sangam era to denote a chieftain. The term Nilaimai has long been part of Tamil usage—for example, inscriptions from the 12th–13th centuries CE mention an individual bearing the title Nilamai Azhagiya Nadalvan. Various 17th-century Sanror historical documents note that Nadalvar is one of the titles associated with the Sanrors, the ancestors of the Nadar community. However, the term Nilaimaikkarar is a comparatively recent development.

Customs and traditions of the Nilaimaikkarars

The Nilaimaikkarars enjoyed the privilege of using the title Nadan, meaning “lords of the land,” since ancient times. Historically, even the Brahmin priests were known to defer to the authority of the Nilaimaikkarars in regions under their control. Customarily, Nilaimaikkarar men rode horses, and their women observed strict gosha, revealing themselves only to the men of their own household. Accordingly, Nilaimaikkarar women travelled in covered palanquins.

The Nilaimaikkarars enjoyed the privilege of using the title Nadan, meaning “lords of the land,” since ancient times. Historically, even the Brahmin priests were known to defer to the authority of the Nilaimaikkarars in regions under their control. Customarily, Nilaimaikkarar men rode horses, and their women observed strict gosha, revealing themselves only to the men of their own household.

Nilaimaikkarars' aristocratic land rights

Sarah Tucker, a 19th-century British observer, noted that among the Nilaimaikkarars, landholding combined formal ownership with a continuing customary claim. Even after selling a parcel of land, a Nilaimaikkarar commonly retained a right resembling a quit-rent. In practice, this meant the purchaser of the parcel became liable to pay the customary residual sum to the Nilaimaikkarar in recognition of his traditional authority over it.

Tucker argued that this arrangement resembled the English manorial system. However, she noted a legal privilege absent in the English model: in land disputes, other castes had to establish title through written deeds, whereas a Nilaimaikkarar needed only to be identified as the traditional Nadan of that tract. Once so identified, the court generally awarded the property to the Nilaimaikkarar unless the challenger could produce proof of purchase.

According to Sara Tucker, even after selling a parcel of land, a Nilaimaikkarar commonly retained a right resembling a quit-rent. In practice, this meant the purchaser of the parcel became liable to pay the customary residual sum to the Nilaimaikkarar in recognition of his traditional authority over it. In land disputes, other castes had to establish title through written deeds, whereas a Nilaimaikkarar needed only to be identified as the traditional Nadan of that tract. Once so identified, the court generally awarded the property to the Nilaimaikkarar unless the challenger could produce proof of purchase.

The Adithan family of Kayamozhi

The Adithan family of Kayamozhi is often regarded as one of the oldest Nilaimaikkarar families, and they claim descent from Surya, the sun god—a lineage also claimed by the ancient Chola dynasty. The Adithan family held special privileges at the Siva temple in Tiruchendur. They financed the construction of one of the temple’s pavilions and covered the costs of various ceremonial expenses. The family also traditionally donated the temple’s large wooden car, and accordingly, they were granted the privilege of being the first to touch the rope used to draw the car through the streets during the festival.

In more recent times, Shiv Nadar—the founder of HCL—is a Nilaimaikkarar from Moolaipozhi, Thoothukudi district. Shiv Nadar's mother, Vamasundari Devi, was the sister of S.P. Adithan, former speaker of the Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly and the founder of the Tamil daily Dina Thanthi. S. P. Adithan was a member of the Kayamozhi Adithan family.

The Adithan family traditionally donated the temple’s large wooden car, and accordingly, they were granted the privilege of being the first to touch the rope used to draw the car through the streets during the festival.

The Nadadhi Nadakkal rulers of Manavira Valanadu

Manadu—formerly known as Manavira Valanadu—corresponds to the southern regions of present-day Tirunelveli and Thoothukudi districts, falling within the Tiruchendur administrative circle. This region comprised numerous Paṟṟus (Tamil for “settlements”), which were further organized into northern and southern divisions.

Several villages today bear names such as Dandupattu, Pallippattu, Nainappattu, Seerudaiyar Pattu, and Chetiya Pattu. Since the term Pattu is equivalent to the Tamil word Paṟṟu (meaning settlement), it is evident that these villages were part of the regions known as Vadapaṟṟu (Northern Settlement) and Tenpaṟṟu (Southern Settlement). Stone pillar inscriptions discovered in Theri, dated 1639 AD, provide evidence that the Vadapaṟṟu region comprised a total of ten settlements. Similarly, the Tenpaṟṟu region included numerous settlements, among which the area referred to as Anju Pattu Nadukal—loosely translated as the Five Paṟṟu Countries—appears to have been part of Tenpaṟṟu.

Ten Nilaimaikkarar rulers—collectively known as Nadadhi Nadakkal—were invested with authority over the ten divisions of Vadapaṟṟu in Manadu by Vadamalaiyappa Pillai, the Nayaka king’s representative, in 1639 AD. Their regnal titles are as follows:

- Ātitta Nadan

- Kōvinta Paṇikka Nadan

- Vīrappa Nadan

- Tīttiyappa Nadan

- Picca Nadan

- Ayyā Kuṭṭi Nadan

- Tikkellāṅ Kaṭṭi Nadan

- Niṉaittatu Muṭitta Nadan

- Avattaik Kutavi Nadan

- Kuttiyuṇṭa Nadan

For the sake of clarity, the above list comprises the regnal titles of the ten rulers of the Vadapaṟṟu region, rather than their personal names. The inscription makes a mention of Ātitta Nadan, the direct ancestor of the aristocratic Adithan family of Kayamozhi in Tiruchendur. These rulers were granted authority to raise, reduce, or abolish taxes in the northern divisions of Manadu. The charter stone recording this decree stands at the center of the Manadu Theri region, now buried partially by sand near the village of Elluvillai. This pillar, measuring approximately five feet in height and two feet in circumference, has weathered to the point that its inscription is largely illegible. The text of this inscription was first published by P. J. Kulasekararaj in 1908 AD. A carved image of the goddess Amman serves as the official seal on the pillar.

Media baron Sivanthi Adithan was a direct descendant of Ātitta Nadan.

The history of the descendants of Ātitta Nadan was systematically compiled. Of the remaining nine rulers, two territorial domains are still identifiable: Paṇikkaṉ Moḻi, which was governed by Kōvinta Paṇikka Nadan, and the settlement of Vīrappa Nadan Kuṭiyiruppu, which was held by Veerappa Nadan. The domains of the other seven Nadans remain untraced—likely buried beneath the shifting sands of the Theri. Following drought and shifts in trade at the close of the 17th century AD, the descendants of these Nadadhi Nadakkal rulers migrated elsewhere. Based on the traditions and royal customs of the Nilaimaikkarars, renowned archaeologist Mr. S. Ramachandran suggests that the Nilaimaikkarars could plausibly be the surviving descendants of the Muvendar dynasty.

Ten Nilaimaikkarar rulers—collectively known as Nadadhi Nadakkal—were vested with authority over the ten divisions of Vadapaṟṟu in Manadu. These rulers were granted authority to raise, reduce, or abolish taxes in the northern divisions of Manadu.

Nadars During Nayak Rule

Although some Nadar rulers acknowledged Madurai Nayak sovereignty, the overall relationship between the Nadar community and the Nayak rulers was not amicable. 17th-century folklore asserts that, after the Pandyan dynasty’s decline, many Nadars intentionally relocated to areas around Tiruchendur and Kanyakumari. A 1662 AD Vikramasingapuram inscription records that Vadamalaiyappa Pillai—acting on behalf of the Nayak king—granted a tax exemption to an Uyyakondar known as Sivanthi Nadan. The Uyyakondars were an ancient Nadar subsect. Yet the same inscription reveals how this Uyyakondar had to petition the Nayak representative for relief from burdensome levies.

A 17th-century copper plate found at Alwarthirunagari by Dr. Thamarai Pandian, which recounts that Vadamalaiyappa Pillai compelled a Pandyan descendant to donate his lands to a local temple. Taken together, these documents suggest that many Nadars migrated southward to evade punitive taxation and social marginalization under the Nayak administration. They maintained a degree of separation from the mainstream caste hierarchy until the Nayak dynasty’s fall—an exodus closely tied to the Pandyan collapse.

Historical documents suggest that many Nadars migrated southward to evade punitive taxation and social marginalization under the Nayak administration. They maintained a degree of separation from the mainstream caste hierarchy until the Nayak dynasty’s fall—an exodus closely tied to the Pandyan collapse.

Conclusion

The history of the Nilaimaikkarars reveals a long-standing continuity of aristocratic identity drawn from the old Sanror community. The surviving inscriptions and village toponyms of Manadu vividly illustrate how the ten Nilaimaikkarar rulers, Nadadhi Nadakkal, once governed and taxed the Vadapaṟṟu settlements under Nayaka patronage. The records of these rulers highlight their prominent role in Manadu. Despite the fact that some Nadars acknowledged the Madurai Nayak sovereignty, 17th-century Nadar folklore and inscriptions suggest that the overall relationship between the Nadar community and Nayak rulers was strained.

See Also

- From oblivion to light: Reconstructing Nadar community's history through recently discovered ancient documents.

- Connecting the Dots: Understanding the Relationship Between the Noble Sanrors and the Nadar Community.

- Valangai Uyyakondar: A Forgotten Chola Clan Whose Heritage and History Connect to the Nadars of Today.

- Unravelling the Historical Misconceptions Surrounding the Nadar Community: The Actual Social Standing of the 19th-Century Nadars.

References

- S. Ramachandran. Valaṅkai Mālaiyum Cāṉṟōr Camūkac Ceppēṭukaḷum. Tamil Archaeological Book. International Institute of Tamil Studies, Government of Tamil Nadu, 2004.

- A. Thasarathan and A. Ganesan. "Māṉavīra Vaḷa Nāṭṭuk Kalveṭṭukaḷ." Tamiḻil Āvaṇaṅkaḷ, edited by A. Thasarathan, T. Mahalakshmi, S. Nirmala Devi, and T. Bhuminaganathan. Tamil Archaeological Book. International Institute of Tamil Studies, Government of Tamil Nadu, 2001, pp. 52-59.

- Hardgrave, Robert L., Jr. The Nadars of Tamilnad. University of California Press, 1969.

- A. Thasarathan. Nilaimaikkārar eṉum piṟkāla Mūvēntar. Part 1. Tamiḻ Ōlaiccuvaṭikaḷ Pātukāppu Maiyam, 2021.

- Annual Reports on South-Indian Epigraphy: For the years 1939–40 to 1942–43. Edited by C. R. Krishnamacharlu, The Manager of Publications, Delhi, 1952. “Report for 1940–41,” plate no. 271 (Kulasekarapattinam, Tiruchendur Taluk).

- Tucker, Sarah. South Indian Sketches: Containing a Short Account of Some of the Missionary Stations Connected with the Church Missionary Society in Southern India, in Letters to a Young Friend. Part I, J. Nisbet & Co., 1842.

- Damodaran, Harish. India’s New Capitalists: Caste, Business, and Industry in a Modern Nation. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

- Padmini Sivarajah."Manuscript tells warriors' tale of Cholas." The Times of India, 18 May 2023.

- "Cōḻar kula Valaṅkai Cāṉṟōr varalāṟu-ōlaiccuvaṭiyil kiṭaitta ariya takavalkaḷ." Nakkheeran, 26 May 2023.

- "Copper plates on 'forced' land donations in Tamil Nadu's Tuticorin temple found." The Times of India, 23 April 2023.