Articles > Published Studies > From oblivion to light: Reconstructing Nadar community's history through recently discovered ancient documents.

From oblivion to light: Reconstructing Nadar community's history through recently discovered ancient documents.

Published Studies

Featured

First published: April 14, 2025

|

Last updated: December 14, 2025

Introduction

For the last three decades, Tamil archaeologists have discovered various palm leaf manuscripts, copper plate documents, and inscriptions relevant to the history of ancient Nadars. The purpose of this article is to elaborate on the significance of these discoveries. This article is based on the research contributions of Mr. S. D. Nellai Nedumaran, Mr. S. Ramachandran, and Dr. A. Thasarathan.

Ancient Nadar historical documents

Sanror community's mythological origin story

Origin stories are mythological narratives, uniquely tied to each community, that recount their ancestral and legendary beginnings. When studying a particular community's ancient history, anthropologists often examine the community's origin story to gain more insights. In order to better understand the information provided by ancient Nadar historical documents, it is important to be familiar with the mythological origin story of the Sanrors, the ancestors of the Nadars [note 1].

Although the Sanror origin story from ancient ballads varies slightly in every version, its central core tells of seven celestial maidens who, while bathing in a pond, caught the eye of the Sage Vidyathara. Using his siddhi (mystical powers), he created a cold atmosphere with rain and upper air currents. After bathing, the maidens, seeking warmth, approached a source of fire. The sage, manifesting himself in the form of fire, united with the maidens, resulting in their immediate conception. Subsequently, the maidens gave birth to seven children. The maidens entrusted their children to the care of Sage Vidyadhara, stating that taking them to their own realm, the underworld, would bring severe consequences. The goddess of war, Bhadrakali, took pity upon them and brought them up as her own sons. Bhadrakali taught her adopted sons the art of war. The story identifies these seven sons as the forebears of the royal Valangai Sanrors. In some versions of the story, the Valangai Sanrors belonged to the Cholan lineage.

One day, the tale goes on, the River Cauvery near the Cholan country breached, and as the city was threatened with flooding, the Cholan king ordered all males to carry earth in baskets upon their heads to rebuild the bund. The Valangai Sanrors, however, refused to obey the king. "We were meant to carry crowns upon our heads, not baskets," they cried. The king was furious and ordered that one of the Sanrors be buried in the sand up to his neck and that his head be kicked off by an elephant. The order was obeyed, and the head, as it was cast into the flood waters, cried, "I will not touch the basket." In a rage, the king ordered that a second be treated likewise, and as the head floated away, it cried, "Shall this head prove false to the other?" The king freed the remaining Sanrors, fearing the wrath of Bhadrakali.

In the 1950s, Robert Hardgrave, an American anthropologist, recorded the mythical oral origin stories of the Nadars, which he obtained from a group of Nadar villagers. Though the story Hardgrave recorded had a few discrepancies—typical of oral lore—it closely mirrored the origin story of the Sanrors. The survival of this story as oral lore among the Nadars clearly implies that the Sanrors are the ancestors of the Nadars. To this day, the Nadars say they will not touch the basket.

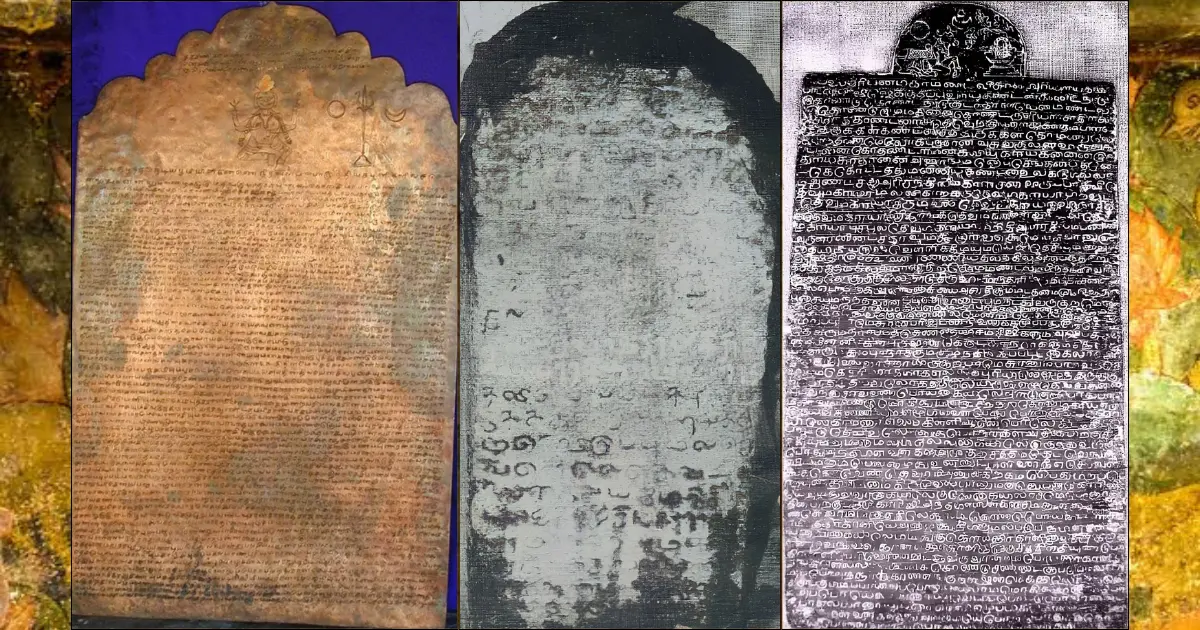

Karumapuram copper plate

17th-century Karumapuram copperplate document

Archaeologist Dr. S. Rasu was the first to uncover the Sanror copper plate inscriptions in the Kongu region. Among the Sanror copper plate documents discovered around the Kongu region, the Karumapuram copper plate document is considered the most significant discovery. The Karumapuram copper plate document was inscribed in the 17th-century (400 years ago) and is currently in the possession of a Hindu monastery in Karumapuram. This monastery has been maintained by Kongu Nadars and Brahmins for many generations. The copper plate document speaks about the glory of the Sanror community. It provides the following key historical details:

- The copper plate document states that the Sanrors were brought up by Bhadrakali and that they are the proud sons of the Saptha Kanniyars, which translates to celestial virgins. This assertion also finds mention in the mythological origin story of the Nadar community and is a vital piece of information, as it proves the link between the Sanrors and Nadars.

- The copper plate document mentions that the Sanrors are a royal race and also states that their emblem is a lion. This assertion is also mentioned by other Sanror copper plates. However, other Sanror copper plate documents affirm that the Sanrors have also used other emblems, such as the tiger and fish.

- The copper plate document affirms that the Sanrors used the title Muppar in the Chera country, the title Gound in the Chola country, the title Nayakar in the Northern country, and the title Nadalvar in the Pandya country.

- The copper plate document states that the Sanrors were known by the title of Booventhiya Cholan. According to Valangai Malai, a 17th-century Sanror historical ballad, the title Booventhiya Cholan was awarded to the Valangai Uyyakondars, an ancient Nadar subsect, for their military prowess. Valangai Uyyakondars were renowned warriors of the Cholan army who were also related to the Cholan dynasty. The Valangai Malai contains intricate details about the Uyyakondars.

- The copper plate document states that the Sanrors are the descendants of the Yenathi clan and further affirms that Yenathi Nathar—one of the 63 Saivite Nayanmar saints—belonged to the Sanror clan. Yenathi Nathar belonged to an ancient Sanror subsect known as Eela Sanrar (pronounced as Īḻac Cāṉṟār). The traditional occupation of Yenathi Nathar's clan, according to the 12th-century book Periya Puranam, was instructing the art of war to soldiers.

- The copper plate document records that the Sanrors had their own currency, and this assertion is also mentioned in other ancient Sanror documents. This currency was later known as Shanar cash.

- The copper plate document states that the Sanrors had the privilege of lake tax exemption and customs tax exemption. This is a clear indication that the Sanrors were a royal land-owning caste.

- The copper plate document colloquially states that the Sanrors don't use their heads, meant to bear crowns, to lift mud baskets. This point is also mentioned in the mythological origin story of the Nadars and hence adds further weight to the fact that the Sanrors and Nadars are the same race.

- The copper plate document states that a Sanror preached to the revered Brahmin saint Adi Shankaracharya and taught him the art of war.

- The author of the copper plate refers to the Sanrors as Saana Kulam, meaning Saana clan in Tamil, and describes a member of the clan as Saana Kula Dheeran, which loosely translates to valiant hero of the Saana clan. The term Saana is the adjectival form of Sanar in Tamil and thus corroborates that the Sanrors are, in fact, the Sanars or Shanars (Nadars)—as Saana serves as an epithet specifically referring to the Sanrors [note 2].

For your reference, follow the Read the Referential Pages link below to read the actual text engraved on the Karumapuram copper plate document. The Karumapuram historical document was inscribed in 17th-century Tamil.

The author of the copper plate refers to the Sanrors as Saana Kulam, meaning Saana clan in Tamil, and describes a member of the clan as Saana Kula Dheeran, which loosely translates to valiant hero of the Saana clan. The term Saana is the adjectival form of Sanar in Tamil and thus corroborates that the Sanrors are, in fact, the Sanars or Shanars (Nadars)—as Saana serves as an epithet specifically referring to the Sanrors.

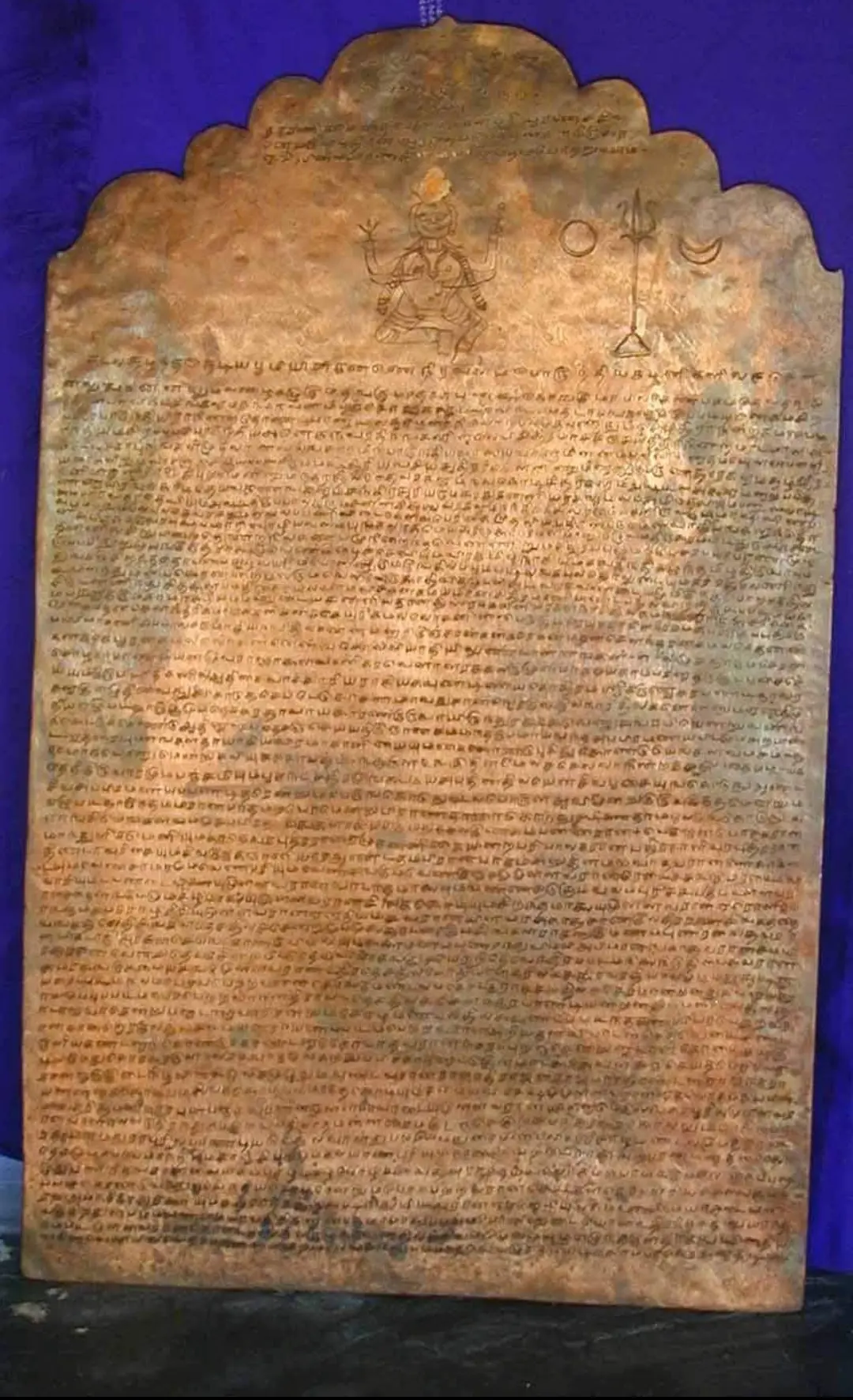

The 17th-century Avalpoondurai Copper Plate Document

The Avalpoondurai copper plate is another important document relevant to Sanror history. This copper plate was inscribed in the 17th-century and is currently preserved in a Sanror Hindu monastery in Avalpoondurai, Erode district. The monastery has been maintained for many generations by the Kongu Nadars and Siva Brahmins. This 400-year-old copper plate records that the Sanrors belonged to the clans of Aditha (or Surya) and Chandra, indicating that the Sanrors and Moovendars shared a common ancestry [note 3]. Furthermore, the copper plate document notes that the Sanrors followed the tradition of using the white umbrella, a custom once associated with Tamil royalty. This piece of information is mentioned in various other Sanror historical documents, including the 17th-century Karumapuram copper plate document.

The Avalpoondurai copper plate document copper plate records that the Sanrors belonged to the clans of Aditha (or Surya) and Chandra, indicating that the Sanrors and Moovendars shared a common ancestry. Furthermore, the copper plate document notes that the Sanrors followed the tradition of using the white umbrella, a custom once associated with Tamil royalty.

Why are these discoveries significant?

Ancient Indians, unlike Europeans, didn't have books containing the ancient history of India. Hence, most Indians of the 17th-century didn't have a lot of knowledge about their ancient history. Early British colonists were very interested in studying the history of India. However, the British had to study the history of India by deciphering various inscriptions, runes, and lost treasures. In short, it wasn't easy for the British colonists to study the history of India.

The Nadars of the 17th-century were not only literate but also knew how to maintain their history. They knew details about wars that were fought centuries ago. The 17th-century Sanror ballad Valangai Malai contains intricate details about the ancient Uyyakondars. Tamil archaeologists discovered inscriptions about the Uyyakondars only recently, and the details provided by these inscriptions match the details provided by the ballad Valangai Malai. This clearly proves that the Nadars of the 17th-century were an advanced community that traditionally maintained their history.

Some Ancient Nadar historical documents

- Valangai Malai (16th-century palm-leaf manuscript).

- Valangai Malai (17th-century historical ballad).

- Vengalarasan's Story (17th-century historical ballad).

- History of King Mulappulikodiyon of Mandalam Kadu (palm-leaf manuscript).

- Ancient King of Mandangkudi, Mandakkendrathiri Losanan's History (palm-leaf manuscript).

- Karumapuram Sanror Copper Plate Document (17th-century copper plate document).

- Avalpoondurai Sanror Copper Plate Document (17th-century copper plate document).

- Thirumuruganpoondi Sanror Copper Plate Document (Inscribed in 1670. A 17th-century copper plate document).

- Perundurai Sanror Copper Plate Document.

- Thingalur Sanror Copper Plate Document.

- Thiruvidaimarudur Sanror Copper Plate Document (17th-century copper plate document).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the discoveries of palm leaf manuscripts, copper plate documents, and inscriptions over the last three decades have profoundly enhanced our understanding of the ancient Nadar community, or Sanrors. These historical records provide vital insights into the community’s origins, royal lineage, military traditions, and socio-political significance. The preservation of their history through these documents demonstrates the advanced literacy of ancient Nadars. By linking mythological tales with historical evidence, these findings not only reaffirm the historical identity of the Nadar community but also highlight their enduring legacy within Tamil culture and history.

Notes

- The terms Sanrar, Sanravar and Sanar are variants of the term Sanror. This is because of a common linguistic feature in Tamil. For instance, the word Kaṉṟu (meaning "calf") and its variant Kaṇṇu are essentially the same word with different pronunciations.

- The Nadars today were previously known as Sanars or Shanars.

- The Cheras, Cholas, and Pandyas were collectively called the Moovendars. The Moovendars belonged to the Surya and Chandra clans.

See Also

- Connecting the Dots: Understanding the Relationship Between the Noble Sanrors and the Nadar Community.

- Valangai Uyyakondar: A Forgotten Chola Clan Whose Heritage and History Connect to the Nadars of Today.

- Ezhunutruvars: Descendants of the Muvendar Lineage, Renowned for Their Role in Governance and Military Service.

- Yenathi: The Clan of the Saivite warrior-saint Yenathi Nathar that traditionally trained the soldiers of the king's army.

- The Velirs and the Sanrors: Comprehending Their Shared Customs, Heritage, and Royal Legacy as Historically Related Clans.

- Shanar Cash: A Historical Perspective on Its Existence, Recognition by Historians, and Mentions in Sanror Documents.

- Avalpoondurai Copperplate: A 400 years old historical document that offers significant insights into Sanror history.

- Uraan Nilaimaikkarars: A Historical and Sociocultural Analysis of an Aristocratic Nadar Subsect.

References

- S. Ramachandran. Valaṅkai Mālaiyum Cāṉṟōr Camūkac Ceppēṭukaḷum. Tamil Archaeological Book. International Institute of Tamil Studies, Government of Tamil Nadu, 2004.

- S. D. Nellai Nedumaran. "Koṅkunāṭṭu Camutāya Āvaṇaṅkaḷ." Tamiḻil Āvaṇaṅkaḷ, edited by A. Thasarathan, T. Mahalakshmi, S. Nirmala Devi, and T. Bhuminaganathan. Tamil Archaeological Book. International Institute of Tamil Studies, Government of Tamil Nadu, 2001, pp. 95-105.

- A. Thasarathan and A. Ganesan. "Māṉavīra Vaḷa Nāṭṭuk Kalveṭṭukaḷ." Tamiḻil Āvaṇaṅkaḷ, edited by A. Thasarathan, T. Mahalakshmi, S. Nirmala Devi, and T. Bhuminaganathan. Tamil Archaeological Book. International Institute of Tamil Studies, Government of Tamil Nadu, 2001, pp. 52-59.

- S. Rasu. Koṅku Nāṭṭu Camutāya Āvaṇaṅkaḷ. Tamil Archaeological Book. Tamil University, Thanjavur, Government of Tamil Nadu, 1991.

- S. D. Nellai Nedumaran. "A note on Cāṇār Kācu." Tamiḻar Kācu Iyal, edited by Nadana Kasinathan. Tamil Archaeological Book, International Institute of Tamil Studies, Government of Tamil Nadu, 1995, pp. 153-154.

- Hardgrave, Robert L., Jr. The Nadars of Tamilnad. University of California Press, 1969.

- V. Nagam Aiya. The Travancore State Manual. Vol. 2, Travancore Government Press, 1906.

- Iyengar, P. T. Sreenivasa. History of the Tamils: From the Earliest Times to 600 A.D. Asian Educational Services, 2001.

- Zareer Masani. "Did Britain Educate India?" Open Magazine, 5 Oct. 2017.

- "Literacy Rate in India 2023." The Global Statistics, theglobalstatistics.com.